Sometimes, the words simply refuse to come. Or they spit out reluctantly, occasionally spraying the screen in explosive gouts of rusty prose in protest at their forced exposure.

At these miserable times, I look around at the rows of books on my shelves, the stacks on my desk, on the floor beside and behind me; I think of the teetering pile beside my bed and I wail “HOW DID THEY DO IT?” (in my head, of course, as it’s usually late at this point and all the sensible people are asleep).

‘They’ are those exotic creatures otherwise known as published authors and ‘it’ is finish a novel. The getting published bit is also of interest but, at this stage, just finishing the damn story is enough to win my deep admiration.

“Ah,” some might say, “You’ve already told us you don’t plan. That’s clearly the problem.”

Maybe so, dear readers. Then again, maybe not.

At this year’s Perth Writers Festival, there was a lot of discussion about process, planning and problems along the way to publication. Some authors did plan and knew the ends of their stories before they began. Others – hallelujah! – did not.

So, in the interests of hope and validation for non-planners like me, as well as an insight into the agonies involved in birthing three very different books, here’s how successful authors Miguel Syjuco, Rodney Hall and Adam Ross did ‘it’.

Miguel Syjuco (Ilustrado) – Knows ending

Miguel Syjuco (Ilustrado) – Knows ending

Syjuco won the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2008 for his first novel, Ilustrado, before it was even published and has been described in The Guardian as “already touched by greatness”.

Ilustrado explores 150 years of Filipino history through a young student’s investigation of a famous Filipino writer whose body is found floating in the Hudson River in the United States. The writer’s life, his investigation into corruption and the life of the Philippines itself, is recreated through extracts from his short stories, novels, newspaper articles, letters and text messages.

Syjuco, who wrote Ilustrado as his PhD project, spoke eloquently at the PWF of his desire for the novel to reflect the cultural melting pot that is the Philippines and its rich history. In a session titled ‘Breaking the Mould’, he admitted the novel was challenging for readers and said he “tried to create a book that wasn’t out to just break the mould but had some very distinct aesthetic and philosophical goals that it had to achieve through its form.”

In this context, it would be remarkable if Syjuco hadn’t planned the complex and ambitious narrative. However, as it turns out, it wasn’t careful planning but inspiration born of despair which saved Ilustrado.

“It took me four years and within that period of time you change your mind an awful lot,” he said. “I had an idea of how I wanted to end the book and that sort of kept me sane because, everywhere else, I was lost. So having an ending helps.”

Even so, Syjuco was unhappy with the original manuscript, a straight narrative of 200,000 words. “It excerpted from Crispin (the writer) randomly almost and it was really unreadable,” he said. “I didn’t even want to read it.”

In despair, Syjuco got stoned, threw himself on a couch and watched a documentary about textile manufacturing in the southern Philippines.

“I know it sounds very obvious but, at the time, it was a real eureka moment,” he said. “They take the different threads, dyed them individually, arranged them in a certain way on the loom and then weaved them together to make patterns and ‘Boom! That’s it, that’s how I’ve got to write my book.’

“So I rushed to the computer, I took apart my manuscript and I spun those individual narrative threads on their own and then arranged them to try to create patterns.

“So that’s the way the book works. There’s no straight Aristotelian rising action-denouement sort of structure. It’s sort of different fragments bumping up against each other creating tension, much in the same way that in jazz music or classical music recurring motifs give the piece shape and formative action, and that’s basically what I tried to do with the book.”

Adam Ross (Mr Peanut) – Knows last line

Adam Ross (Mr Peanut) – Knows last line

Ross went one step further than planning the end of his novel. From the start, he knew the very last line: “All the way to her heart”.

“That was my lodestar,” Ross said. “But the middle was long and hard. I always work that way. I have a very clear idea of where I’m going but the connective tissue from the beginning to the end is the toughest part of the process and it requires a great deal of faith. So I sometimes put things down for a long time.”

Inspired by a conversation with his father about a suspicious death in the family, as well as a large and recent dose of Alfred Hitchcock, Ross sat down and wrote the first three chapters of Mr Peanut “pretty much verbatim”. Then he got stuck.

Mr Peanut is the story of a computer game designer who fantasises about his wife dying. When she ends up dead, he is the prime suspect. Ross created two detectives to investigate the murder – one who believed everyone he interrogated was innocent, the other that everyone was guilty. It didn’t work and the novel languished.

“I had written myself into something that I didn’t fully understand at the time and then what subsequently occurred was essentially a 12-year process of figuring out what I had started,” he said.

Over the next several years, Ross learned the true story of Sam Sheppard, a doctor convicted of killing his wife in 1954 and who inspired the television series The Fugitive, which got him thinking about perceived roles in marriage and eventually led to the creation of a new detective character.

Ross also came across the work of MC Escher – famous for ‘impossible’ artworks and those where one image can be seen to morph into another – as well as the two-sided concept of the mobius strip, which put him in mind of a person walking on the floor, which to another person was the ceiling.

“What I was trying to figure out was a way to bend the expectation or change the reader’s posture to the narrative,” he said. “What I needed was that big picture and what happened was, it was the character of Mobius, who is either a private investigator or hit man a la Hitchcock’s Stranger On The Train. He is the character that binds every narrative and has different meanings for each individual.

“So that was the eureka moment and then I had these massive white boards in my office. I had these massive diagrams of how to string Mobius as inter-connective tissue. This was the form I arrived at. The book is a giant mobius strip.”

The long road to Mr Peanut has since been vindicated by a glut of positive reviews and all important buzz. The Guardian’s Christopher Tayler said the book was stuffed with wit and stylistic tricks and Stephen King said it gave him nightmares.

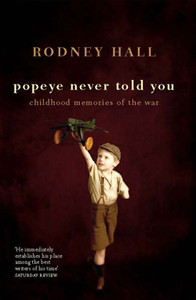

Rodney Hall (Popeye Never Told You) – Does not plan!

Rodney Hall (Popeye Never Told You) – Does not plan!

Hall has had more than 30 books published and has won the Miles Franklin Award twice. He writes by hand. And he does not plan.

“I never know where to go,” he told the PWF session. “I start from the germ of an idea in conversation or something but I allow them to guide me where they are going. They all behave totally differently.

“I have maybe 14 or 15 begun books, some of which got to almost completion, like maybe 150 pages, before they told me they were going nowhere. Sometimes just one chapter or even one page.”

Not only does Hall not plan, he also doesn’t change his words around once they’re written.

“I never change the order,” he said. “The only way I can be secure about how the reader’s feeling is in that moment when the writer is closest to being his or her own reader and that’s the moment you get the words, each sentence, on the page.

“For that reason, I never ever change the order of anything because if I tamper with that, I’ve tampered with whether I can feel where the audience is. So I always take things as they evolve and so my books tend to be, some of them are very long. And I love that in other people’s books.”

Hall’s latest book, Popeye Never Told You, is a memoir of his time living in a small town in the west of England, aged 5 to 9, during the World War II.

He wanted to capture those very clear childhood memories before they faded. So, about five years ago, Hall sat down and wrote a standard autobiography which explained what happened to him, how it affected him and put it all into historical context.

“That was about a 200-page book and I sat with this really uncomfortable thing, like a homunculus on my back, because I fundamentally hated it,” he said.

“It’s terribly difficult to write about yourself, especially if you have a lifelong discomfort with yourself. I mean I, for example, hated my name, the name I was given. I hated it so much that i was about 40 before I could happily answer the phone using it. I don’t know why I hung on to it and didn’t change it. I’ve never been very comfortable with it and so I was very uncomfortable with the idea of an autobiography.”

Unsure what to do, Hall asked “a brilliant young Melbourne writer” to read the manuscript and his verdict was a blunt “Look, I’m not interested in this at all.” According to Hall, his friend went on to say: “Every time the little boy is there it suddenly comes to life. But when you tell us what it all means, who cares? Second World War, who cares what the German bombers were doing? Why they were dropping bombs, I don’t want to know.”

That was the turning point. Hall decided to include only the child’s experience in the book. No history, no context, no story.

“My project in the breaking of the mould was to avoid at all costs any kind of narrative at all,” he said. Hall assembled his memories so they interacted but they were still a collection of tiny parts.

“You don’t just read through because you’re not going to get a story, you’ll get a sequence of events,” he said. “But read the gaps because you’ll see that you see, hopefully, a lot more than the little boy is showing you, tells you.”

Hall was not the only author at the PWF to endorse the ‘let the story go where it will’ approach, but the planners out-numbered them by a long way.

I don’t care. It works for him so it can work for me. Now, if only the words will come.

Eaton was the only one of the three to have deliberately included Australian landscapes in his work. Nightpeople was his PhD thesis, in which he set out to write a distinctively Australian fantasy. The book was set in a post-apocalyptic landscape. Australia plus apocalypse equals a literary Mad Max, right? Wrong. So wrong. Like saying cabernet equals grape juice.

Eaton was the only one of the three to have deliberately included Australian landscapes in his work. Nightpeople was his PhD thesis, in which he set out to write a distinctively Australian fantasy. The book was set in a post-apocalyptic landscape. Australia plus apocalypse equals a literary Mad Max, right? Wrong. So wrong. Like saying cabernet equals grape juice.

David Whish-Wilson

David Whish-Wilson

Toni Jordan

Toni Jordan